When I read the 11 September posting to Suerk, he reiterated with clarity something he'd attempted to put into words once before. I wrote it down. Here's what he said.

Anyone who knew Jim Smith well has random memories that are funny, absurd, and like his life itself, contradictory. Ask someone like me who loved Jim deeply, and you will get an unending parade of humor, tenderness, joy and passion. One only has to look at his wife, Carol, and their three children to get the nature and scope of this great man.

I miss my faithful, loving friend.

Suerk's dear friend Kitty Whitty wrote me yesterday to share a piece Jo Schlegel wrote to honor Jim. Here is Kitty's introduction to Jo's words. Suerk would want me to share this with all who follow the blog.

From Kitty:

Jo Schlegel recently posted a tribute to Jim Smith she wrote on Facebook. It is beautiful. I share it here and hope you will share it with Suerk. Some of the details are different, of course, but this is exactly the way I feel about Suerk and Jay Quinn. They 'gave me the keys.'

From Jo Schlegel:

Jim Smith gave me the keys.

Jim entrusted me with keys to big, heavy doors, large wooden crates, backstage rooms, and secret entrances to Gothic structures. I could steal away at almost any hour to hack through some massive toccata and fugue at the organ in the Chapel. Or, at the grand piano on stage in Boone Hall, I could end a disciplined practice session by sight-reading some Rachmaninoff prelude audaciously, extemporaneously (in the sense of having no regard for the metronome), and with preposterous fingering. And why not: the ghost light was there to shoo away any imaginary detractors and other bogeymen. Alone and undisturbed in these dimly lit performance spaces, I was free to contemplate a life in music – even as whatever noise I had just presumed to make reverberated through the gigantic hall. Spend even a little time practicing under those conditions and you realize there’s no point having the keys or sitting at the keyboard unless you intend to make echoes you and the ghosts can stand to listen to. No one else has given me that kind of space. Only Jim Smith.

A life in music, or a life without music. “Do, or do not. There is no try.” Sure, it holds: Jim was my Yoda. If only he could have lived nine hundred years.

Our nickname for him was Schmutley. Hannah and Sarah may not remember, but the class of ’81 had an embarrassment of riches in two inimitable imitators: Nick Fuhrman (who I understand makes a great Watergate Caesar salad) and Alex Iden, the Click and Clack of Marshall and Irving. Greet either declamation legend with a curt clearing of the throat, a la Walter Burgin, and one could be treated to a commercial-free marathon of all thirteen episodes of their Emmy-winning Season One, each beginning with the signature line, “Ahem. We. Begin. Again.” No faculty member, fac brat (including Ted Smith), or dining hall worker was sacrosanct (“Breakfast is over, you’re going to have to go sit in the alcove, I’m going to have to tell Mr. Hoppe”), and the legend built up to a command performance at a school assembly. What I wouldn’t give to have that material on DVD.

Walter, as headmaster, was a natural touchstone; the cough became a sort of class greeting. But it was Schmutley who provided some of the richest material for Alex and Nick’s schtick. Alex could conjure up James Winston Smith with a slumped shoulder and an asymmetrical, wrenched smile that would instantly remind me of wry critiques of choral entrances, deliberate mispronunciations and malapropisms, and Jim’s protective yet storied relationship with Bryan Barker. (Yes, there were impressions of Bryan.) It got kind of meta when Jim started doing Alex’s impression of Jim, so you’d get this exaggerated snarl of a smile. That’s when you knew he really cared.

Bryan was still the school’s carillonneur in those years, playing brilliantly from memory, quoting Byron verbatim. But he was also starting to drive through brick walls and ring in jubilant Easter mornings in the middle of the night in Lent. Jim confided in me that there just weren’t that many carillonneurs, so he figured he would learn. Indeed, I could hear Jim practicing up in the tower once in a while when I was in the Chapel, and seem to remember climbing up into the tower to watch one of them play. It was like something out of a P.D. James mystery.

Many of my piano lessons were in the house on Seminary Street, and there was always some creature or another passing through that beautiful room – tow-headed toddlers, older brothers, small dogs, and sundry Winebrenners and their derivatives. In my fact-challenged memory the piano is made of mahogany, sits on museum-quality oriental rugs, and is surrounded by custom-built bookshelves crammed with first editions. The dogs are in love with the furniture.

I sang in the chorale and the madrigal singers, and participated in Wednesday chapel services. Jim started the women’s ensemble while I was a student. I remember some repertoire: Liebeslieder Waltzer; Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols; Jim’s Happy Birthday arrangement (which I recently found); Jim’s composition “Surely the Lord Is In This Place,” which I’d love to have if it’s been preserved; trying to sing “I Know that My Redeemer Liveth” at the Easter sunrise service. I remember not wanting to sing the final verse of “The Times They Are A Changin’ “ at baccalaureate because it seemed disrespectful of parents. I remember lots of madrigals in various languages. I remember a trip to the outskirts of Baltimore for some kind of singing pageant that seems to have lasted several weeks although I’m sure it was just a weekend; and the unforgettable powder-blue polyester dress with the six-inch ruffle collar that passed for concert attire. Very Karen Carpenter. It was also that weekend that I learned the term “swing choir.”

Jim was that compassionate taskmaster who held people to their highest expectations of themselves – not out of compulsion, but out of respect for people’s talents. Jim embodied the school’s ideal of “integritas” by inspiring people to be true to themselves. It wasn’t about enforcing major school rules; it was about fulfilling your potential. There was never any question whether you would. Jim, where were you when I needed you in college, surrounded by people who are now household names?

He gave me the keys. They opened doors to vast spaces, architecturally inspired, acoustically brilliant, inhabited by great minds and musicians of our time. Majestic spaces accessed not through grand entrances but through back doors, stage doors, performers’ entrances, passageways to stages and choir lofts and balconies and towers. Iron gates and steam tunnels at Yale. At Trinity Church in Boston, the stairs behind the choir loft which led to the then-unfinished undercroft, past some cats and boxes of archives, up into a small restroom, out into the vestibule and up into the back balcony, from which I would magically appear to sing little solos at Candlelight Carol Services over the years. The stage door at Symphony Hall, where a security guard buzzes you in to a heavily painted basement passageway that smells like the cleaning fluid they used to use in elementary schools. The Shed at Tanglewood, with its industrial concrete backstage area that seems like an unlikely aesthetic in which to meet Bryn Terfel or Andre Previn or Christopher Plummer or my husband. At Carnegie Hall, where you enter on 56th Street, show a badge, and take a service elevator to a top floor for warmup; then wend your way down many staircases, action movie style, to enter stage right and look up, suddenly breathless at the reality of where you are and who’s there with you. Even stage entrances to places like the KKL Luzern or the Royal Albert Hall, where you might meet Kenneth Branagh in line for coffee. The view from the risers, in whatever venue – maestro’s face; the soloists’ backs. Seiji’s kinesthetic genius – the way he gives cues with his pinky, his hair, his tongue. Levine’s way of coaxing great singing out of people without ever making them feel tense. Even the informal spaces, the chapels at vacation spots, the outdoor performances, the gatherings around pianos, the sendups and parodies. Jim gave me the keys.

A life with music. And the space in which to contemplate what sorts of echoes the ghosts might enjoy. Because if you’re going to spend all that time in all that space, you might as well make a decent sound.

27 September 2009

11 September 2009

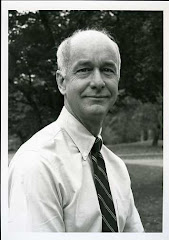

Jim Smith

Suerk had intended to dictate some words regarding the loss of his friend Jim Smith. He has stopped suggesting he wants to offer the words, and after encouraging him for a two weeks, I have stopped encouraging him. He is simply unable. Larry Jones will see to it that Suerk receives a recording of Jim’s memorial service. Suerk is looking forward to hearing the words others use to honor Jim, and especially looking forward to hearing the good music that honors all who are able to attend the service. In lieu of Suerk’s words, here’s Jim’s obituary.

James Winston Smith

James Winston Smith, 70, former member of the Mercersburg Academy faculty, died peacefully in his home the evening of August 20, 2009.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland on May 11, 1939, he was the son of Helen Tilghman Smith and James Winston Smith. He grew up in College Park and Laurel, Maryland.

A graduate of High Point High School in Beltsville, Maryland, he graduated from the University of Maryland and Westminster Choir College in Princeton, New Jersey, where he earned a Master’s in Music.

He began his music career at St. Mark’s School in Dallas, Texas, before coming to the Mercersburg Academy in 1965.

During his 36 year tenure at the Academy he served as teacher, organist, choirmaster and choral director. He was Head of the Fine Arts Department for five years and developed the Mercersburg Academy Chorale and Woman’s Ensemble. He was also a longtime member of the American Guild of Organists.

In 1981 he was appointed the Academy’s carillonneur. He played the bells nationally and internationally, ultimately achieving status as a Carillonneur Member with the Guild of Carillonneurs of North America.

In 2008 he was honored with the dedication of the James W. Smith Memorial Bell, the final bell in the Academy chapel’s 50-bell carillon.

Mr. Smith was very active in the local community. He was a longtime member of the Franklin County Heritage Society, helped create the Historic District in Mercersburg and served as President of Mercersburg’s Borough Council for many years.

Surviving are his wife, Carol; a brother, Winslow; a son, Ted; two daughters, Hannah and Sarah; and four grandchildren.

A memorial Service will be held Saturday, September 12 at the Mercersburg Academy Chapel at 2 p.m.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be directed to the Mercersburg Academy, c/o The James W. Smith Memorial Fund, 300 E. Seminary Street, Mercersburg, PA 17236

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)